The passing of Al-Hajj Dr. Yusef Abdul Lateef, 93, on Dec. 23 in Massachusetts brings to mind the exotic, semi-forgotten influence of Islam on the American music scene in the 1950s, when Islam, and specifically Ahmadiyya Islam, was cool.

Lateef was born William Emanuel Huddleston on Oct. 9, 1920, in Chattanooga and grew up in Detroit, where his father changed the family name to Evans. He began as a saxophonist in 1946, then went on to play the flute, oboe, bassoon, and many other instruments. In a very long and important career, he made music with such renowned figures as Cannonball Adderley, Donald Byrd, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charles Mingus, as well as being a band leader in his own right.

Yusef Abdul Lateef died at 93 on Dec. 23, 2013. |

Lateef become one of the first black jazz musicians to associate with Islam, converting in 1948 and changing his name at that time, then twice going on the pilgrimage to Mecca and writing a PhD dissertation in 1975 titled "An Overview of Western and Islamic Education." As an implicit indication of his piety, from 1980 on he banned alcohol from his performances.

Missionaries of the small Ahmadiyya movement out of Pakistan had eye-popping success among leading jazz musicians of the 1950s, converting in addition to Lateef such other jazz luminaries as Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Nuh Alahi, Art Blakey (Abdullah Ibn Buhaina), Kenny Clarke (Liaquat Ali Salaam), Fard Daleel, Mustafa Daleel (Oliver Mesheux), Talib Daoud, Kenny Dorham (Abdul Hamid), Gigi Gryce (Basheer Qusim), Ahmad Jamal (Fritz Jones), Abbey Lincoln (Aminata Moseka), Muhammad Sadiq, Sahib Shihab (Edmund Gregory), Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith, Dakota Staton (Aliya Rabia), Argonne Thornton (Sadik Hakim), McCoy Tyner (Sulaiman Saud), and Abdul Wadud.

Dakota Staton, aka Aliya Rabia (1930-2007). |

One annotated listing of Muslim jazz players includes 75 players; another listing contains about 125 names. These musicians preferred to perform at clubs owned by fellow Muslims, many of whom hailed from the Caribbean. In short, Islam was the unofficial religion of bebop.

The musicians turned to Islam in part for genuine religious reasons; in part because (in the words of a 1953 Ebony article), "Islam breaks down racial barriers and endows its followers with purpose and dignity"; and in part because Islam served them as a mark of distinction in a United States where Muslims numbered only about 100,000 out of a population of 150 million.

Comments:

(1) This connection contains a certain irony, given the Muslim role in enslaving Africans and Islam's dubious and sometimes directly hostile attitude toward music. For example, when the singer British Cat Stevens first converted to Islam in 1977, he stopped recording music for two decades. For a time in 2010, Somali Islamists not only banned all music but even school bells. Their counterparts in Mali in 2013 banned mobile phone ringtones.

(2) Ahmadis also harbor reservations about music, especially what they call pop music (which presumably includes jazz): Replying to a question on this topic, Mirza Tahir Ahmad, the fourth caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, replied in 2010:

it all depends on the degree of the habit and the nature of the music. The music in itself, as a whole, cannot be dubbed as bad. ... In these things it is a matter of taste. ... as far as pop music is concerned I don't know how people can tolerate that! Just sheer nonsense! I don't disrespect music altogether, because I know the classical music had some nobility in it. ... the taste left behind by this modern "so-called music" is ugly and evil, and the society under its influence is becoming uglier and more permissive, more careless of the traditional values, so this music is obviously evil and sinful. ... an occasional brush with music which draws you into itself at the cost of higher values, at the cost of memory of Allah, at the cost of prayers, where you are taken over by music and that becomes all your ambition and obsession; if that happens then you are a loser, obviously.

(3) The Islam of the bebop era enhanced the musicians' cool factor and was apolitical.

(4) That stands in sharp contrast to American Muslim music of subsequent years, which is characterized by alienation and anger. In the 1990s, for example, the Nation of Islam could count on the support of Ice Cube, King Sun, KMD, Movement X, Queen Latifa, Poor Righteous Teachers, Prince Akeem, Sister Souljah, and Tribe Called Quest. The Five Percenters, a splinter group of the Nation, had in its corner Grand Puba, Big Daddy Kane, Eric B. and Rakim, and Lakim Shabazz. Normative Islam also had a smattering of artists such as Soldiers of Allah. Mattias Gardell, a biographer of Louis Farrakhan, finds that the "hip-hop movement's role in popularizing the message of black militant Islam cannot be overestimated." (December 27, 2013)

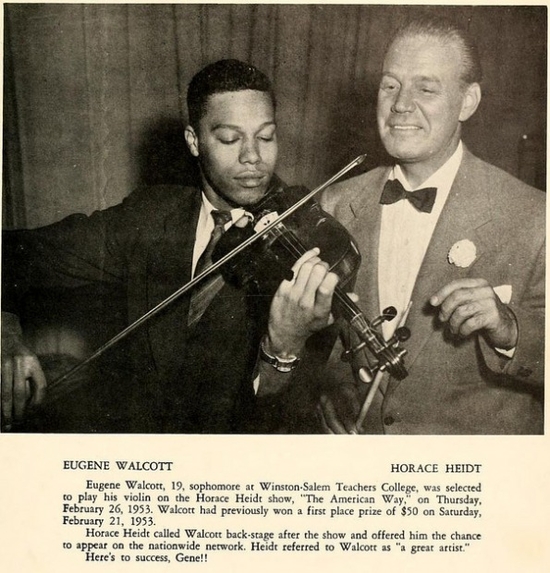

Louis Farrakhan was a talented violinist when young and still Eugene Walcott. He made his mark in the late 1950s with theatrical and musical creations, the only ones the Nation of Islam countenanced in its early decades. |

Dec. 27, 2013 addendum: Readers inform me:

- The soul singer Joe Tex converted to the Nation of Islam and became Yusef Hazziez. Max Roach cooperated with the NoI.

- Yusef Lateef performed in Israel.

- Writes Joshua Teitelbaum of the Hoover Institution: "It is true, Lateef did not allow alcohol during the performance, but they made that announcement before the show, so there was enough time, for those who wanted it, to run out to the bar next door and get a drink first."

Plus, jazz may have a deep connection to Muslim music from Africa, as Jonathan Curiel argues in "Muslim Roots, U.S. Blues." One paragraph:

The trading of African slaves led to a diaspora unlike any other in human history, with at least 10 million Africans bought and sold into bondage in the Americas. The pain felt by those slaves is evident in American blues music—a music that's often about cruel treatment, sad times and a yearning to break free. Blues music is a unique American art form that went around the world and, in turn, influenced history. Without the blues, there wouldn't be jazz and there wouldn't be the bluesy music of the Rolling Stones and the Beatles.

Mar. 28, 2018 update: The famous April 1953 Ebony article, "Moslem Musicians: Mohammedan religion has great appeal for many talented progressive jazz men," has been posted here. An excerpt:

There are today a large number of Negro Americans who have embraced the Moslem faith. They perform the daily prayer ritual, observe the dietary laws laid down by the prophet and each sundown turn their faces toward Mecca. Slightly more than 200 of this number are jazz musicians, mostly on the "modern kick."

The American Negroes who have rejected Christianity for the Moslem way have explanations for their conversion that cover a wide range of spiritual, personal and emotional factors. There is among the new Negro Moslems here a unity of thought on one point: Islam breaks down racial barriers and endows its followers with purpose and dignity.

Like members of the Nation of Islam, they claim not to be subject to Jim Crow regulations, and seem to be convincing:

Lynn Hope, a spectacular tenor saxophone player, has travelled widely through the South with his band and claimed that the segregation laws do not apply to him or his brothers. "We are recognized as whites in the South and are not Jim Crowed," Hope says. "We do not accept Jim Crow laws or regulations." ...

Hope and his men, wearing their turbans, enter a restaurant with superb aplomb, and are usually told very quickly, "We don't serve colored people here." Hope's answer is swift, calm and always the same: "We are not Negroes but members of the Moslem faith. Our customs are Eastern: We claim the nationality of our Arabic ancestors as well as their culture." Almost invariably, they receive courteous treatment.

A caption adds that "Hope is a favorite with crowds even though many believe his Mohammedanism is strictly for commercial reasons." Many decades later, that may sound unlikely but Langston Hughes endorsed this skepticism in a short poem, "Be-Bop Boys":

Imploring Mecca

to achieve

six discs

with Decca.

Dec. 8, 2019 update: Inspired by this article, Peter Manseau put together a concert titled "Islam and Modern Jazz." (Click here for the program.) It took place this evening at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. I attended and thoroughly enjoyed it.

The "Islam and Modern Jazz" concert at the Museum of American History in Washington. |