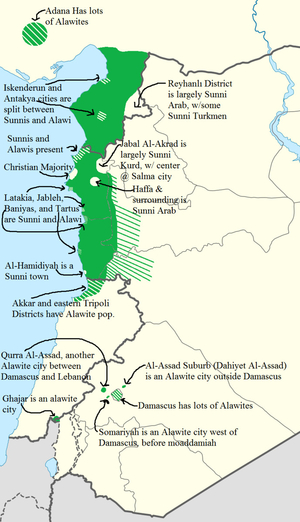

Solid green indicates an Alawite majority and partial green a significant Alawite minority. |

In brief, throughout the centuries, the Alawites stood out as Syria's most isolated, impoverished, despised, and oppressed ethnicity. Only when generals from their community seized power in Damascus in 1966 did the power balance change in their favor. But the Alawites' ruthless domination of Syria for the next 58 years caused the country's majority Sunni Muslim population to rebel, leading to a full-scale civil war that began in 2011 and ended in December 2024, when Sunnis overthrew Alawite rule and returned to power. Recent events point to an ominous Sunni desire for retribution.

Alawites Oppressed, Pre–1920

As is well known, Islam claims to be the final religion. Accordingly, it abominates any subsequent faith originating from within it, calling its adherents apostates and deeming them fit to be sold into slavery or executed. (Because Judaism and Christianity predate Islam, their followers are tolerated but assigned an inferior status.) Sunnis and Shiites alike historically reviled Alawism, a distinct new religion that emerged from Shiite Islam in the ninth century AD.They looked upon Alawites (also known as Alawis, Nusayris, or Ansaris) as apostates and subjected them to harsh discrimination.

Thus, the prominent theologian Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058-1111) wrote that Alawites "apostatize in matters of blood, money, marriage, and butchering, so it is a duty to kill them." Ahmad ibn Taymiya (1268-1328), a major continuing influence on Islamists, called Alawites "more infidel than Jews or Christians, even more infidel than many polytheists" and deemed them to "have done greater harm to the community of Muhammad than have the warring infidels." Therefore, he concluded, "war and punishment in accordance with Islamic law against them are among the greatest of pious deeds and the most important obligations" for a Muslim.

Such views persisted into modern times. Sunnis called them monkeys. The Ottoman Empire required them to pay extra taxes. A nineteenth-century Sunni shaykh, Ibrahim al-Maghribi, decreed that Muslims could freely take Alawite property and lives. A British traveler, Frederick Walpole, recorded being told, "these Ansayrii, it is better to kill one than to pray a whole day."

Frequently persecuted and sometimes massacred in the modern era, Alawites insulated themselves geographically from the outside world by remaining within their highland in the northwest of Syria—between Lebanon and Turkey—in what are now the provinces of Latakia and Tartous. In the late 1920s, less than half of one percent of Alawites lived in towns. This isolation had terrible implications. A leading Alawite shaykh described his people "among the poorest of the East." French geographer Jacques Weulersse observed that they lived out "their solitary existence in secrecy and repression." Samuel Lyde, an Anglican missionary, found the state of their society "a perfect hell upon earth."

The Alawite Rise to Power, 1920–1970

The Alawites' half-century rise from oppression to domination began with their initial resistance to the French incursion, but they later helped the occupation of Syria (1920 to 1946) by supplying intelligence and providing a disproportionate number of recruits to the military and the police. In turn, French rule benefited the Alawites with autonomy and other privileges. After Syria gained independence from France in 1946, Alawites initially resisted central government control, but by 1954, had reconciled themselves to Syrian citizenship. Taking advantage of their continued overrepresentation in the army, they began their political ascent.

Ironically, the discrimination that had kept the Alawites in the lower social ranks served them well through the multiple military coups d'état that wracked Syria between 1949 and 1963. Ruinous power struggles among senior Sunni officers accompanied the regime changes, severely depleting Sunni ranks. Standing apart from these conflicts, non-Sunnis, and particularly Alawites, benefited by inheriting the Sunnis' positions. Further, while Sunnis entered the military as individuals, Alawites did so as members of clans, with officers bringing kinsmen into their ranks.

Alawites also acquired power through the Baath Party, founded in 1940, which they joined in disproportionately large numbers: in part because one of its three founders was an Alawite and in part because two of its central doctrines, socialism and secularism, widely appealed to them. Socialism offered economic opportunities to the country's poorest community, while secularism—the withdrawal of faith from public life—promised relief from religious prejudice.

Alawites had played a major role in the Baath coup of 1963, taking many key positions and purging Sunni competitors. These developments culminated in 1966, when a group of mainly Alawite Baathist military officers seized power. Once in office, they further purged non-Alawite officers. In the final drama, two Alawite generals, Salah Jadid and Hafez al-Assad, battled for supremacy, a rivalry that ended when Assad prevailed in 1970 and became the country's president in 1971. This—Syria's tenth military coup d'état in seventeen years—ended the era of instability and culminated the Alawites' rise to power.

Alawite Rule and Sunni Shock

Confessional affiliation remained vitally important during the 58 years of Alawite rule, mostly under Hafez al-Assad (1970-2000) and his son Bashar (2000-2024). Hafez built a brutal police state and imposed Alawite control by placing his co-religionists in the armed forces, the party, the government, the civil bureaucracy, and, above all, the intelligence services: "Alawites so prevailed as undercover agents that people feared naming the sect in public," reported the New York Times in 2011. "The preferred euphemism was 'the Germans'." Over time, Assad narrowed the range of his key allies, surrounding himself not just with coreligionists but with fellow tribesmen and members of his own family.

Sunnis made up about 70 percent of Syria's population until the outbreak of civil war in 2011 (which led to their mass emigration). Beyond their numbers, they had historically ruled the region, leading to the tacit assumption that they should enjoy the perquisites of power. Like Episcopalians in the United States, they saw themselves as non-ethnics in a heterogeneous society. Before 1914, Sunnis held nine-tenths of administrative posts, maintained their predominance during the French mandate, and inherited control of the government upon independence. After 1970, however, they were mostly relegated to window-dressing. In the pithy words of an army veteran, "An Alawite captain has more say than a Sunni general."

The psychological impact of this reversal on Sunnis can hardly be exaggerated. To them, an Alawite ruling in Damascus compares to an Untouchable becoming maharaja or a Jew becoming tsar—an unprecedented and shocking development. Michael Van Dusen of the Wilson Center rightly calls this shift in power "the most significant political fact of twentieth-century Syrian history and politics."

Alawite Rule and Sunni Opposition, 1966–2024

Sunni Muslims overwhelmingly perceived Assad's totalitarian repression in sectarian terms. The assertion of Alawite power in 1966 provoked the Sunnis' religious anxieties, as reflected in their outraged response to a 1967 article that condemned Islam as "a mummy in the museum of history." The reaction included large protests, the arrest of Sunni religious leaders, wide-scale strikes, and considerable violence. In 1979, the opposition came near to overthrowing the regime with the massacre of some 60 cadets—almost all Alawites—at a military school, followed by the near-assassination of Assad himself in 1980.

Just when it appeared that the regime might fall, Assad responded with devastating effectiveness. Efforts to destroy the Muslim Brotherhood peaked in early 1982, when Syrian troops assaulted the city of Hama, attacking Muslim Brotherhood strongholds with field artillery, tanks, helicopters, and 12,000 troops (almost all Alawite). The soldiers indiscriminately killed as many as 30,000 Sunnis, ending serious challenges to the regime for nearly three decades.

Sunni opposition during those decades did not disappear but became more careful and patient. Indeed, Sunnis' grievances festered as they endured domination by a people they considered inferior; as they perceived discrimination in aspects of daily life (such as Sunni households paying four times more than Alawites for electricity); as they lived with the memory of Hama and other massacres; as they resented the socialism that reduced their wealth, the military powerbrokers who destroyed their patronage system, the authoritarian rule that effaced political expression, the supposed indignities against Islam, and the regime's alleged cooperation with Maronites and Israelis.

The Assads endeavored to present themselves as Muslims but few if any Syrian Sunnis accepted this claim. A rich body of evidence points to the rulers being near-universally perceived primarily not as Arabic-speakers, Baathists, pan-Syrianists, pan-Arab nationalists, or anti-Zionists but as Alawites. In 1973, demonstrators called for an end to "Alawite power." The Muslim Brotherhood initiated a campaign of terror against what it called "the sectarian, dictatorial rule of the despot Hafez al-Assad" in 1976. In 1983, the National Alliance for the Liberation of Syria accused Assad of "a burning hostility to Arabs and Islam."

King Faisal of Saudi Arabia (center) and Hafez al-Assad (with prayer beads) prayed in Damascus on July 18, 1975. |

Traditional roles and attitudes in effect reversed: Sunni hostility toward Alawite power echoed the historic Alawite hostility toward Sunni power. Drawing on both old and new grievances, the two groups came to loathe each other, creating a vicious circle. As Sunnis became increasingly alienated, Alawites depended ever more on Alawites to rule. As the regime took on an increasingly Alawite cast, Sunni discontent deepened.

(That said, it bears noting that academic analysts of Syria have almost universally rejected what the University of London's Eberhard Kienle describes as a crude "popular caricature of a government purely by and for all Alawis," and what the University of New Hampshire's Alasdair Drysdale calls a "reductionist" focus on ethnicity.)

Civil War and Sunni Hostility, 2011–24

When the region-wide Islamist rebellion of 2011 reached Syria, it triggered a hideous 14-year—mainly Sunni—insurrection against Bashar al-Assad's government. The civil war resulted in an estimated 7.5 million internally displaced persons, 5.2 million external refugees, and approximately 620,000 deaths. International involvement exacerbated the war's sectarian nature, with the Shiite Islamic Republic of Iran and Lebanon's Hezbollah helping the government, while Sunni Türkiye supported the rebels.

Domestically, the regime relied increasingly on its Alawite base to the point that Sunnis came to equate "Alawite" with "Assad-regime supporter." Reuters recounts how Assad "sent army and secret police units dominated by [Alawite] officers ... into mainly Sunni urban centers to crush demonstrations calling for his removal." Meanwhile, Sunni conscripts "refused to fire at their co-religionists," making the army unreliable for internal repression. The shabiha, a mostly Alawite plainclothes security force, took over many of its duties, engaging freely in vandalism, terror, and murder. In turn, the Jabhat al-Nusra organization—the predecessor of Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), today's rulers—participated in massacring Alawite civilians.

Specific incidents steadily exacerbated Sunni-Alawite tensions. For example, according to Syrian refugees in Lebanon:

Before sunrise one August morning [of 2011], electricity in [an unnamed Syrian] village was cut and armed forces swooped in. ... Among those taking part in the raid were people they said they recognized from a neighboring Alawite village who had joined pro-Assad militias known as the shabiha. ... Seventy-five people were arrested in the village that day, according to the family. The bodies of two were returned to their families and, of the others, three have not been heard from since.

In another incident, in 2012 the shabiha focused on a single street in the town of Taldou, and, as the military looked on, mowed down 45 members of a single extended family. Some quotations capture the intensity of hostility this aroused among Sunnis:

- Adnan al-Arour, a Sunni religious leader, referring to Alawites opposed to the Sunni uprising: "I swear by God we will mince them in grinders and feed their flesh to the dogs."

- Mamoun al-Homsi, a Syrian Sunni leader: "you despicable Alawites" ... "From this day on, we will not remain silent. An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth. ... I swear that if you do not renounce that gang and those killings, we will teach you a lesson that you will never forget. We will wipe you out from the land of Syria."

- Muhammad: "The people in this regime are forcing us to hate Alawites."

- Mustafa, a barber: "Assad developed and modernized the country for himself and the interests of his sect."

- Farid Ghadry, head of the Reform Party of Syria: Many Syrians "are seething with anger over the Alawite-led government's butchering of Sunnis."

- Cherif Abaza, a former member of Parliament: "If you are a Christian or an Alawite, you will be slain."

- Ibtisam, an 11-year-old Sunni refugee living in Jordan: "I hate the Alawites and the Shiites. We are going to kill them with our knives, just like they killed us."

- Ahmed, 12-years old: "The Alawites say, 'Kneel in front of my shoe.' We can't be free with Assad because he kills us."

- Heza, 13-years old: "After the revolution, we want to kill them." Asked whether that included a child their own age, Heza replied, "I will kill him. It doesn't matter."

Civil War and Alawite Fear, 2011–24

In 2015, Syria's future leader Ahmed al-Sharaa promised to protect Alawites but only if they agreed to "correct their doctrinal mistakes [i.e., abandon the Alawite religion] and embrace Islam." At that point, he said, they would "become our brothers" and benefit from his protection. Such statements, not surprisingly, scared the small Alawite community. A 2011 report from Homs described a "harrowing sectarian war" spreading across the city, which had become divided into Alawite and Sunni residential areas:

Though some Alawites support the uprising, and some Sunnis still back the government, both communities have overwhelmingly gathered on opposite sides in the revolt. ... the struggle in Homs has dragged the communities themselves into a battle that residents fear. ... Alawites wear Christian crosses to avoid being abducted or killed when passing through the most restive Sunni neighborhoods.

Sunnis returning to reclaim their residences in Homs heightened Alawite fears. Wild rumors spread, such as that of an apocryphal female butcher in Homs who asked armed Sunni gangs "to bring her the bodies of Alawites they capture so that she can cut them up and market the meat."

The New York Times reported that "Many Alawites are terrified; they are often the victims of the most vulgar stereotypes and, in popular conversation, uniformly associated with the leadership." Ghadry wrote that Alawites fear "the Muslim Brotherhood sharpening their knives for the kill." Dread simultaneously compelled the regime to make survival its top priority and the Alawite population to depend more heavily on the regime.

Worse, many Alawites also suffered under the Assad regime. Wafa Sultan, an exiled physician, recounts the many injustices, including intentional impoverishment (to ensure their sons would serve the government to earn a living), the persecution of intellectuals, and the imprisonment of dissidents' relatives. Some, like one Alawite religious figure, reported that "the Alawite community is living in a state of great fear" and predicted that the regime's collapse "will place us at the mercy of fierce reprisals." Already in 2012, a teacher accurately predicted that the Assad regime, which "is using us ... will run away, and we will pay a heavy price." Despite that price, many Alawites rejoiced at Assad's fall. In sum, Sunnis saw themselves as fighting an infidel tyranny, while Alawites saw themselves under existential threat.

Sunni Hostility, 2025–

Then came the stunning events of early December 2024, when the Sunni Islamists of Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham, under the leadership of Ahmed al-Sharaa, along with its allies, swept rapidly through Syria and within days seized Damascus. Assad fled to Russia.

Forces loyal to Ahmed al-Sharaa at the Mediterranean coast in Latakia on March 9. |

The first three months of the new regime saw some Sunni retribution against Alawites but in a limited and unorganized way: firings from jobs, vigilantism, and small-scale violence. In late January, for example, Syrian journalist Ammar Dayoub documented incidents "from directing sectarian curses at Alawites and Shiites to gathering the men in the squares and flogging them, smashing furniture in people's homes, stealing gold and silver and acts of violence against women." Reuters reported a pattern of Alawites being ejected from their own homes, with a human rights group identifying "hundreds, if not thousands, of cases of evictions."

In one instance, on January 24, government gunmen arrived in the largely Alawite town of Fahil in a convoy of SUVs and pickup trucks, some mounted with machine guns. They "went house-to-house ... dragging Alawite men to their deaths," in the Washington Post's description, killing 16 Alawites associated with the prior regime, including one general. They also pulled passengers off a bus, asking them, "Are you Alawite?" and, in some cases, murdered those who answered in the affirmative.

In response, the regime "did not acknowledge these violations [but] blamed individuals or small local factions." Further, MEMRI reports, "It also refrained from publishing the names of those responsible, thus preventing the families of the victims from taking legal action against them." This predicament led to the formation of Alawite "resistance groups," which the regime promptly vilified as "Assad loyalists."

Sunni forces depart Idlib on March 8, heading toward Latakia to fight the Alawites. |

Then, on March 6, 2025, large-scale assaults erupted, mostly in the Alawites' home provinces of Latakia and Tartous—where, according to a 2017 study, Alawites make up 58 and 69 percent of the population, respectively—and in Damascus. Sunni forces, including the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army and foreign jihadists, rampaged through Alawite areas, torching homes and killing indiscriminately.

The HTS government presented itself as defending the country against an insurgency of "Assad loyalists," a spin the international media and even serious analysts widely accepted. But Alawites, who had suffered greatly under Assad family rule and especially during the civil war, abandoned Assad en masse in his hour of need when they could have saved him. Three months later, as Assad languished in Russia, Iranian support had collapsed, and Israeli forces had demolished all the old regime's arsenals, Alawites did not fight a rearguard action for him. Rather, attacks by "resistance groups" against government forces stemmed from fears of persecution. (Rami Makhlouf, a cousin of Bashar al-Assad and perhaps Syria's richest person, implausibly but provocatively claimed to have recruited 150,000 fighters to protect the Alawite community in Latakia and Tartous.)

During the civil war period, Sunnis could freely express rage at Alawites. But in 2025, they came under pressure to be on their best behavior to help Sharaa convince foreign NGOs and governments to accept and aid his regime. However, digging beneath the surface makes clear that the March attacks were acts of vengeance for what one Sunni religious scholar, Abdallah Khalil al-Tamimi, described as the killing of two million Sunnis by "the Alawite regime ... on sectarian grounds." Gareth Brown of the Economist witnessed firsthand a "call to jihad" in the mosques and elsewhere, prompting thousands of people to pick up their guns and rush to Alawite-majority areas. In Damascus, a radio host "encouraged his listeners to cast the Alawites into the sea." Videotapes captured some of these sentiments, such as an HTS-affiliated commander shouting:

Oh warriors of jihad, do not leave any Alawite, male or female, alive. Slaughter the most respected men among them. Slaughter the most respected women among them. Slaughter them all, including children in their beds. They are pigs. Seize them and throw them into the sea.

When a formerlly HTS-affiliated imam, Yahya Abu al-Fath al-Farghali, promoted the idea of relocating jihadists and their families to Alawite-majority areas, he hinted at an ethnic cleansing.

Alawites Oppressed, 2025–

Proud of their actions, many Sunni perpetrators recorded videos of their actions, such as killing two sons in front of their mother. "This is revenge," cried a man looting and burning Alawite homes. Sunnis humiliated Alawites, the Economist reports, forcing them "to bark like dogs, sitting on their backs, riding them, and then shooting them dead." Others showed "dozens of bodies with bullets to the head ... lined up in villages outside of Latakia" or "the bodies of Alawites being dragged behind cars through the streets." Videos commonly feature triumphant yells of "Allahu Akbar," the Islamic battle cry of jihad. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reports collecting "many testimonies" that "perpetrators raided houses, asking residents whether they were Alawite or Sunni before proceeding to either kill or spare them accordingly," a pattern confirmed by Amnesty International. Such incidents amount to collective punishment against Alawites, regardless of whether they helped or opposed the Assad regime.

Alawites testified to their plight. A doctor told of entire families "being wiped out" as Sunnis "entered homes and carried out mass killings of all Alawites." One person described Sunni jihadists "roaming house to house, killing occupants in summary executions and pillaging what they could find. Another explained that "They are killing us, targeting the Alawites. They cursed us, shot at us, burned our property. They are forcing people at gunpoint to sign over their money, homes, and cars. ... They are dropping barrel bombs from planes onto our villages. They loot homes and burn us alive after carrying out mass executions by gunfire and slaughter." Concerning the "barrel bombs from planes," the New York Times reports that government forces deployed helicopters outfitted with both machine guns and repurposed Russian-made anti-submarine depth charges.

Another form of persecution, still shadowy, has emerged: the abduction of young Alawite women. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) reports 50 such disappearances in the first three and a half months of 2025. While the disappearances recall the abduction of Yazidi women in Iraq, they does not appear to have reached the same levels in terms of numbers or sexual abuse, though incidents of torture have been reported.

An in-depth New York Times investigation into events in Baniyas uncovered a massacre of some 1,600 victims, mostly Alawites. "Over three days, gunmen went house to house, summarily executing civilians and opening fire in the streets. ... At least some government soldiers deployed to restore order also participated in the killings." After the killing spree, "Bodies were everywhere. Sprawled across living room floors. Hunched over in citrus orchards. Lying bloodied on roads." To prevent Alawites from escaping Baniyas, the gunmen established checkpoints. In response, some Alawite women wore hijabs to pass as Sunnis when confronted with the inevitable question, usually asked threateningly and repeatedly, "Sunni or Alawite?"

Fear extended even to corpses. As one Alawite near Homs testified, "Near our house, there are 15 bodies, and nobody has the courage to remove them since yesterday." Amnesty International reports that "Families of victims were forced by the authorities to bury their loved one in mass burial sites without religious rites or a public ceremony."

While the violence subsided after early March, incidents of harassment, shakedowns, and attacks continued, with SOHR counting approximately three killings per day. Polling by the Economist finds Alawites about seven times more pessimistic than Sunnis regarding Syria's future, an outlook prompting many to emigrate. In mid-April, the United Nations counted 30,000 Alawites fleeing to Lebanon. Interviews with them indicate despair about developments in Syria and no intention of returning. Russia's Foreign Ministry confirms that more than 8,000 Syrians, mostly women and children, took refuge at its Hmeimim Air Base in Syria. A 36-year-old from Latakia, hiding in an abandoned building summed up the predicament: "As an Alawite, I don't see a future here in Syria."

Proud of their actions, many Sunni perpetrators recorded videos of their actions, such as killing two sons in front of their mother. "This is revenge," cried a man looting and burning Alawite homes. Sunnis humiliated Alawites, the Economist reports, forcing them "to bark like dogs, sitting on their backs, riding them, and then shooting them dead."

In the face of this carnage, Sharaa serenely responded: "What is currently happening in Syria is within the expected challenges." ... "We must preserve national unity and civil peace." ... "We call on Syrians to be reassured because the country has the fundamentals for survival." He also set up a commission of inquiry. Meanwhile, Al-Monitor reports that HTS' ally in Ankara blamed "clashes as an attempt by Iran and Israel to weaken Sharaa's government" and promised to ramp up its support for him.

Western acceptance brings many financial and other benefits. That HTS leaders had emerged from Al-Qaeda and ISIS lends an air of theater to their donning blazers or suits and ties, then embracing happy talk about human rights and blaming violence on the Alawites. In fact, the massacres of early March cast additional doubt on HTS' sincerity. As Dina Lisnyansky of Tel Aviv University notes, "It's very clear that if the central regime did not want these things, they would not happen, because these are not just local Islamist initiatives. Those taking part in the killings have fought for years under al-Sharaa's command. They're not suddenly rebelling against al-Sharaa. They're simply continuing the ideology." Her colleague Michael Milshstein goes further: "You saw his men in action during the massacre."

Foreign Responses

During the quarter-century from independence until Hafez al-Assad's seizure of power (1946-70), Syria served as a battleground for its stronger neighbors, a predicament captured by the title of a famed 1965 book, The Struggle for Syria. After four decades of despotic stability (1970-2010), the civil war of 2011-24 revived the struggle for Syria, this time hosting multiple domestic armed factions, several regional forces (Turkish, Iranian, Israeli), and two great powers (Russia, the United States).

But this renewed struggle for Syria differs in one major respect from the earlier one: the then almost-routine oppression of Alawites has turned into something far more harrowing. One Alawite source estimates the victims to number in the tens or even hundreds of thousands. Indeed, some analysts already refer to the situation as a genocide. The Kurdish Syrian writer Mousa Basrawi decried "an organized campaign of genocide ... aimed at exterminating the Alawites." Christian Solidarity International issued a "genocide warning" due to the "orgy of targeted killings accompanied by dehumanizing hate speech."

A rare demonstration on behalf of the Alawites, in Los Angeles on Apr. 26, 2025. |

And Western governments? Washington "condemns the radical Islamist terrorists, including foreign jihadis, that murdered people in western Syria in recent days." Canberra "condemns the recent horrific violence in Syria's coastal region" and is "deeply concerned by UN reports that many civilians from the Alawite community were summarily executed." The United Nations denounces "harrowing violations and abuses."

Contradicting these fine words, the meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Sharaa resulted in the lifting of American sanctions on Syria without any apparent conditions or demands regarding the security of Alawite or other minorities. Except for Israel, it appears that outside powers have entirely abandoned them.

U.S. inaction during the 1994 Rwandan genocide led to subsequent apologies (Bill Clinton: "I express regret for my personal failure"), as did Dutch failures a year later in Bosnia (Defense Minister Kajsa Ollongren: "We offer our deepest apologies"). The present danger to Syria's Alawites is clear: will politicians once again be content merely to apologize after the fact?

Daniel Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is the founder of the Middle East Forum. This article draws on his three books about Syria as well as a 1987 analysis titled "Syria After Assad." © 2025 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

June 4, 2025 update: For more on this topic, see my blog, "Updates on the Persecution of Alawites."