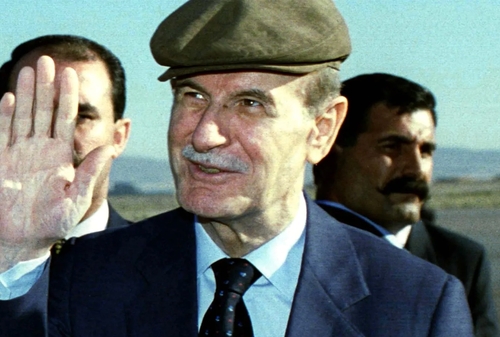

Recent photographs of Hafiz al-Assad, the strongman of Syria, show him gaunt and sickly. Indeed, Assad has been ill since late 1983 and his health, judging by pictures, shows a steady deterioration. This raises questions about Syria when Assad dies? Who follows him and what are the consequences?

An unhealthy-looking Syrian dictator. |

For Syrians, it is a question of particular importance, for Assad has transformed their government. When he came to power in 1970, the country had experienced two decades of almost annual coups d'êtat. No ruler had established himself securely and the country suffered from a weak international position. Assad ended this instability and weakness, imposing strong leadership through a police apparatus, providing continuity of rule, and making Syria a leading actor in Middle East politics.

From what one can tell from the outside, Assad has anointed no successor; when he dies, a number of leading figures will contest the rule. If this occurs, there is a good chance that his whole apparatus of repression will collapse. Syrian politics would then revert to their old ways, as officers stage coups and factions proliferate.

An understanding of the political dynamics of Syria - and the likely prospects after Assad - means grappling with that country's ethnic politics. Other considerations - economics, conflict with Israel, ties to the Soviet Union - matter too, to be sure, but not so much as the fact that Assad and almost all of the present leadership are members of a small and traditionally scorned religious minority, the Alawis. Their rule is profoundly resented by the majority Syrian population, the Sunni Muslims. A serious weakening of the regime could lead to a reassertion of Sunni power and a transformation of Syrian politics.

Alienating the Sunnis

Sunnis make up about a 90 per cent majority of Muslims around the world, and almost 69 per cent of the population of Syria. In addition, they have a long tradition of political power; Sunnis expect to rule. When they do not, trouble usually ensues.

Traditionally, Sunnis did rule in Syria. They long formed the landlord class and owned the great commercial enterprises. Sunnis held nine-tenths of the administrative posts in the years before 1914 and, despite efforts to disenfranchise them by the French imperial power, they virtually maintained this power through independence in 1946. At independence, it was they who inherited the government. Through subsequent changes in government and shifting ideologies over the next twenty years, the conservative and wealthy Sunnis of Damascus and Aleppo controlled the capital.

The Alawis took power in 1966; the impact of this event can hardly be exaggerated. An Alawi ruling Syria was an unprecedented development shocking to the majority population that had for so many centuries monopolized power. It meant the end of the urban Sunni elite's domination and the reversal of many deeply held assumptions and long-standing relationships. The rise to power of this despised minority signaled, as Michael van Dusen has written, "the complete social, economic and political ruin of the traditional Syrian political elite." Van Dusen does not exaggerate when he calls this event "the most significant political fact of twentieth century Syrian history and politics."

Between 1966 and 1970, Alawis increasingly monopolized key political and military positions, a process that culminated with Hafiz al-Assad's seizure of power in 1970. Assad surrounded himself with fellow tribesmen and his own family; they staffed everything from the bodyguard to high positions of state. In February 1971, Assad took a step deeply distasteful to Sunnis when he pushed aside the nominal Sunni head of state and assumed the presidency for himself.

Alawis have benefited from the Assad regime in many ways. Making up for past discrimination, they now receive opportunities out of proportion to their numbers. In 1978, for example, 97 out of the 100 students sent to the U.S.S.R. from Tartus province were Alawi, 2 were Sunni, and 1 Christian. According to an opposition source, 286 out of the 300 students training in the artillery school in Aleppo in June 1979 were of Alawi origins. Such favoritism also makes it possible for Alawis to staff and take over at all levels, not just in the armed forces, but also in the bureaucracy.

The bulk of government spending has been concentrated in Latakia, the poorest region of Syria and the one where most Alawis live. Among the major capital projects are a transportation network, industrial plants, and irrigation works. Syria's third university, Tishrin, was established in the city of Latakia. The government put up money for the Meridien hotel chain to build a luxury hotel in Latakia. Even U.S. aid has been funneled to Latakia.

The bulk of government spending has been concentrated in Latakia, the poorest region of Syria and the one where most Alawis live. Among the major capital projects are a transportation network, industrial plants, and irrigation works. Syria's third university, Tishrin, was established in the city of Latakia. The government put up money for the Meridien hotel chain to build a luxury hotel in Latakia. Even U.S. aid has been funneled to Latakia.

Government contracts have spawned a wholly new class - rich Alawis. Under patronage of the state, they have made their presence felt in parts of Syria in which they never previously lived. The Assad government has bestowed large tracts of land outside Latakia on Alawi peasants, especially in the Homs and Hama provinces. Alawis have moved into the cities in large numbers, and have become a majority of the population in Homs. Working for the government has also taken Alawis to all parts of Syria.

Alawis were traditionally maltreated by the Sunni majority, and their present behavior is widely perceived as revenge for centuries of abuse. Muta' Safadi, a Ba'thist, recounts his experience in the Mazza jail:

There were hundreds of prisoners in the Mazza after 18 July [1963, the date of an abortive coup in Syria], and I was one of them. No one remembered anyone like the prison warden, who gave free reign to torture and probing. During hundreds of nights, his escort did not hold back on the whip or electricity or punches or slaps, or insults against beliefs with the most malicious phrases. Despite this, the attentive among the prisoners understood the conspiratorial plan. They therefore prohibited themselves from hating every Alawi - even though the warden was an Alawi, as was the leader of the torture team. Most of their assistants were Alawis who showed their Alawi-hood by abusing the beliefs of those being tortured.

Twenty years later, non-Alawis found it harder to hold back. Riyadh at-Turk, a leader of the Communist Party of Syria, explained in 1983: "Psychologically there are already two states, one Sunni and the other Alawi. A veteran of fifteen years in the Party left us to rejoin his Alawi clan. . . . Even I, a Communist, a Marxist-Leninist, experience a certain mistrust when I see an Alawi." Not everyone displayed the forbearance of these two men; resentment against Alawis has grown very strong indeed.

A vicious circle set in: Sunni Arabs became increasingly alienated, so the rulers closed ranks and came to depend even more on Alawi support; and as the regime took on an increasingly Alawi cast, Sunni discontent deepened. At the same time, the need to please Alawis reduced the government's ideological character. Pan-Arab nationalism virtually disappeared as catering to the Alawis became the paramount concern. By the mid-1970s, Assad's rule had degenerated into arbitrariness and favoritism.

In addition to Alawi control of the state and its resources, three specific aspects of life under Alawi rule deeply upset Sunnis: secularism, socialism, and foreign policy.

Secularist policies, which call for the exclusion of Islam from public life, are bad enough; this led, for instance, to the abolition of classes about Islam in the schools. Worse was the fact that Alawis were the ones carrying out this policy. Many Sunnis found it intolerable when Alawis called Islam outdated and denigrated its practices.

A socialist order benefited Alawis and other poor rural peoples while hampering the Sunni merchants. The expansion of the public sector went against the capitalists and alienated the traditional urban elite. The nationalization programs of 1965 and later years destroyed the great Sunni families of Syria's cities. Their rationale was stated explicitly by an Alawi officer; he is reported to have explained that socialism "enables us to impoverish the townspeople and to equalize their standard of life to that of the villagers. ... What property do we have which we could lose by nationalization? None!"

External involvements also had adverse effects on communal relations within Syria. Three arenas - Lebanon, Israel, and the PLO - have special importance.

Damascus' 1976 alliance with the Maronites against the Sunnis of Lebanon aroused anger and fear among Syrian Sunnis, who responded by devising dark conspiracy theories about Alawi intentions. They suspected the Alawis of "joining their forces to those of the Maronite Crusaders against the Muslims of Lebanon." They accused Assad of working with the Maronites and Zionists to face the Sunnis. Fundamentalist Sunnis initiated these accusations - a preacher in Damascus attacked the rulers as "impious" for their actions in Lebanon and was thrown in jail - but they quickly spread to Sunnis of all outlooks.

Assad's stance vis-à-vis Israel also caused him problems domestically. Before coming to power in 1966, the Alawis showed little interest in the conflict against Israel and Assad has been criticized for inadequate fervency against Israel. At the same time, he has been widely condemned for anti-PLO policies. As the Charter of the Islamic Front in Syria put it: "Although most of the regimes in the region took part in serious practices against the Palestinian case and the resistance, the sectarian regime in Syria outstripped them all in its indulgence in this crime." The National Alliance for the Liberation of Syria accused Assad of "a burning hostility to Arabs and Islam" and asserted that "all his crimes are in the interest of the Zionist enemy." The Muslim Brethren go further, discerning "an international Jewish-Alawi conspiracy" against Sunni Muslims in general and Palestinians in particular. It goes so far as to claim that "collusion between the Assad regime and the Zionist enemy" underpins the whole of Syrian foreign policy.

Looking forward to the day the Alawis lose power in Damascus, Sunnis believe that Assad is laying the groundwork to break off a part of Syria to form into a separate, Alawi-dominated state. One rumor has it that they are preparing the isolated Jazira region (in northeast Syria) as a refuge. Another sees the region from Latakia to Tartus as an Alawi bastion. Some point to the settlement of 40,000 Alawis in the north Lebanese town of Tripoli as a first step toward an enlarged Alawi state along the Mediterranean coast. According to Annie Laurent: "The day when danger compels the Alawi community to withdraw to the mountains from which they come (in the northwest of Syria, along the Mediterranean coast), the Alawi state will no longer be an academic hypothesis and Tripoli might become its southern end." Yasir Arafat has asserted that the Alawis moved by the Syrian regime to northern Lebanon were brought from Alexandretta, Turkey. The settlement of Alawis in Hama after the massacre there in February 1982 was pointed to as part of this plot.

The stories that circulate among Sunnis about their Alawi rulers appear implausible to an outside observer. But it is precisely this that makes matters so explosive: anything can be believed, nothing strikes the Sunnis as too outlandish.

Muslim Brethren Opposition

Sunni agitation began soon after Alawis moved into positions of power. From the beginning, it was led by the Muslim Brethren and had a religious cast. The Muslim Brethren in Syria is an organization dedicated to establishing a government in accordance with the tenets of fundamentalist Islam. But the fact that Sunnis view the Alawis as non-Muslims means that it would be premature to try to apply Islamic laws in Syria; rather, the first goal has to be the elimination of Alawi rule. Thus, the appeal of the Muslim Brethren lies in its ability to rally anti-Alawi sentiment - and has little to do with its fundamentalist cast. Sunnis join the Brethren because it provides the largest and most durable organization to combat rule by non-Muslims.

Two forms of evidence support this conclusion. First, there is reason to believe that a substantial proportion of the Brethren membership is not only non-fundamentalist Muslim, but even unobservant; thus, a repentant member of the Muslim Brethren, Ahmad al-Jundi, stated in an interrogation televised in Syria that he neither prayed nor kept the Ramadan fast. Second, the Brethren's willingness to work with left-wing and other non-fundamentalist groups in the National Alliance for the Liberation of Syria - including pro-Iraqi Ba'thists and followers of Gamal Abdel Nasser - indicates that its first priority is to destroy the Assad regime, not to impose an Islamic order.

Muslim Brethren activities began in October 1963, led by Isam al-Attar. Violent incidents began two months later, provoked by such incidents as the ripping up of a religious book by a school teacher. More threatening to the state were a series of challenges early in 1964, beginning with a clash between Alawi and Sunni students in Banyas and a commercial strike in Homs. The troubles peaked in Hama, sparked by the arrest of a student for erasing Ba'th Party slogans from a blackboard. This precipitated riots, a commercial strike, and the shelling of a mosque, killing at least 60 Sunnis.

Sunni apprehensions mounted with the consolidation of Alawi power after the February 1966 coup. These explain the Sunni response to an April 1967 article in the army magazine which condemned Islam as an impediment to socialism and "a mummy in the museum of history." Large demonstrations took place in all the major cities, leading to the arrest of many religious leaders, wide scale strikes, and considerable violence.

The rule of Hafiz al-Assad had contrary effects on the Sunni opposition. He initially won the good will of Sunnis by easing economic and religious pressures. Commercial restrictions (which mostly affected Sunni merchants) were relaxed, private enterprise was permitted more scope. Landlords felt less squeezed and Damascenes rose to positions of prominence in the government. The Alawi rulers did their best to fit in, visiting mosques and even performing the minor pilgrimage to Mecca. They quickly gave up the effort to withdraw Islam from the constitution. Foreign policy goals were scaled down and the army was depoliticized.

Note the prominent pictures of Hafiz al-Assad outside the Tawhid Mosque in Aleppo. |

But Assad's rule also crystallized Alawi rule and made it long-lasting. The passage of time exacerbated Sunni discontent and the stability of Assad's rule foreclosed the possibility of quick change, spurring Sunni Muslim antagonism. Further, life in Syria became less pleasant in the mid-1970s. The economy suffered from an imbalance between imports and exports, a brain drain, insufficient internal generation of capital, excessive military expenditures, over-dependence on oil-related revenues, and too much state interference. Social inequities and cultural repression both increased. Syrian forces were aiding the Maronites in Lebanon.

The Muslim Brethren became more active in opposing what they called "the sectarian, dictatorial rule of the despot Hafiz al-Assad." They made impressive gains, for example, in the local elections in 1972. During demonstrations in 1973 reacting against a new constitution, slogans called for an end to "Alawi power." But these acts did not get them far against the solidly entrenched Assad regime. So, in September 1976, the Brethren initiated a campaign of terror. Three years later, their guerrilla warfare came near to overthrowing the regime. The Sunni revolt climaxed with two events: the June 1979 massacre of over sixty cadets - almost all Alawis - at a military school in Aleppo and the July 1980 near-assassination of Assad himself. Not without reason, foreign newspapers in those months featured headlines such as "Time Runs out for Assad," "Crumbling Regime in Syria," and "Bleak Future for Assad Regime."

Just when it appeared that the regime might fall, Assad responded with devastating effectiveness. Efforts to destroy the organization peaked in early 1982, when Syrian troops assaulted the city of Hama, attacking Brethren strongholds with field artillery, tanks, air force helicopters, and 12,000 troops (almost all Alawi). The soldiers, who did not even try to focus on Muslim Brethren members, indiscriminately killed about thirty thousand Sunni Arabs - one tenth Hama's population. This massacre ended the immediate Muslim Brethren challenge and won the rulers a new lease on life. The Brethren saw what the regime would do to protect itself with "steel, fire, rope, and gallows," and the next several years were quiet.

But the Sunni opposition did not disappear, it only became more careful and more patient. Writing in 1983, Gérard Michaud observed, "today it appears that the repressive machinery has succeeded in dismantling the fundamentalist movement in Syria. But for how long? And at what price!" Indeed, after four years of quiet, the fundamentalists began to attack the government again in early 1986.

Conclusion

Sunnis have a long list of grievances against Alawi rule. They dislike the domination of power by a people considered to be socially and religiously inferior. They resent the socialism which reduces their wealth, the indignities against Islam, the attacks on the PLO, and what they perceive to be cooperation with Maronites and Zionists. They live with the memory of Hama and other massacres.

This hostility weighs heavily on the leadership; indeed, bedrock Sunni opposition remains the Assad regime's greatest and most abiding problem. As a small and divided minority, the Alawis know they cannot rule indefinitely against the wishes of almost 70 per cent of the population. Further, the traditional place of Alawis in Syrian society and the manner of their ascent this century both make Alawi power likely to be transient. That Sunni Muslims see Alawi rule as an aberration probably bears on the future of political power in Syria as much as anything else.

In the likely event that the ruling elite fights among itself after Assad dies, Alawi weakness could provide the needed opening for Sunnis to reassert their power. The resentful majority population will fully exploit any faltering by Alawis. The effects will be severe; as one analyst has observed, "in the long run, it is highly dangerous for the Alawis. If they lose their control, there will be a bloodbath." It seems likely, therefore, that Assad's demise will be followed by a change in regime and profound changes in Syrian political life.

Mar. 30, 2011 update: I update this topic at a blog, "'Syria After Assad': Sunnis vs. Alawis."

Dec. 8, 2024 update: Almost thirty-eight years later, Sunnis have overthrown Bashar al-Assad, finally starting the era of "Syria after Assad."