I would like to tell you about my mother.

She was born Irena Eugenia Roth in Warsaw on Nov. 28, 1924. Her father was a businessman with I.G. Farben, the largest company in Europe; her mother was a renowned beauty and the first female automobile driver in Warsaw. Her sister Hanna came along two years later. The family lived in downtown Warsaw, close to her maternal grandparents, owners of a leather-goods store.

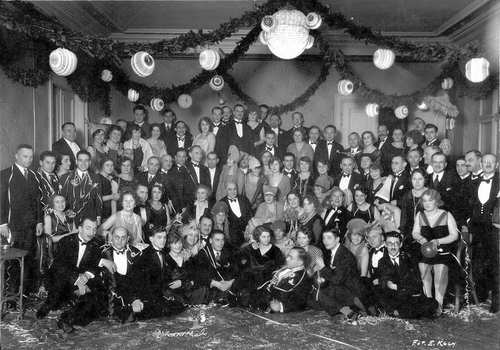

As this family sketch suggests, Irene had a good life in Poland. Photographs attest to the elaborate skits she performed with her sister. She enjoyed after-school treats with her grandmother at an elegant pastry shop. Her parents attended white-tie parties boasting an elegance we hardly can imagine nearly a century later. When she compared notes with her future husband, Richard Pipes, who lived not far away and whom she later met at Cornell University, they found they had attended the same birthday party.

A 1930s Warsaw party. Both my maternal and paternal relations attended. |

Then, of course, it all came crashing down. The Nazis invaded Poland on Sep. 1, 1939, when Irene was 14. Her father was arrested (ironically) as a German citizen and the family fled by car to the northeast. Miraculously reunited with him, they flew together to Stockholm and from there, took a ship to New York City, landing on Jan. 27, 1940. After spending an eye-opening weekend on Ellis Island, they entered the United States.

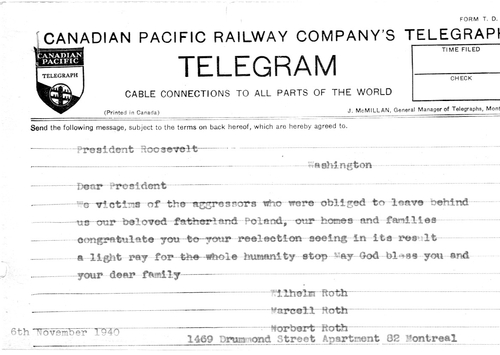

Thanks to a brother of her father who had the foresight to get out before the invasion, the family had the means to set themselves up, first on Drummond Street in Montreal and then on Central Park West in New York. With astonishing speed, the family learned English and entered American life. To give you a sense of their assimilation, I'd like to read the full text of a telegram sent by my grandfather and two of his brothers on Nov. 6, 1940, a day after Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected to the presidency for the third time:

To President Roosevelt, Washington. Dear President, We, victims of the aggressors who were obliged to leave behind us our beloved fatherland Poland, our homes and families, congratulate you on your reelection, seeing in its result a light ray for the whole of humanity. May God bless you and your dear family.

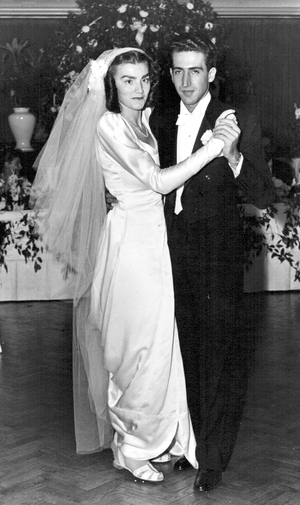

Although a self-described party girl, my mother fit well enough into the academic life in Cambridge and accompanied my father as he rose over the next decade to full professor. Setting up house successively in Boston, Watertown, and Belmont, they acquired a New Hampshire country house in 1959 and moved into a grand house near Harvard Square in 1964. They owned a house on the Caribbean island of Tortola for two decades and then a small Key Biscayne condo in 2014. The first of four grandchildren was born in 1979; others came in 1985, 1987, and 2000. The first great-grandchild arrived in 2018.

Sabbaticals took Richard and Irene to Paris, London, and Palo Alto. A stint with the Reagan Administration meant living in Washington for two years, 1981-82. Richard retired from Harvard in 1996.

Richard and Irene dancing at their wedding. |

Richard died of old age in 2018 but still Irene gainfully kept things going on her own, maintaining three residences, the magazine subscriptions, and the friendships. But it was not the same without him. Also, as she reached her mid-90s, she showed great frustration at not having the capabilities of someone about 70: "I am not myself today," came her ritualistic complaint, "what's wrong with me?" She tried to assert her independence, an increasingly difficult task. She died peacefully at 98 years this morning: at 10:45am, July 31, 2023.

Some reflections, first about the family and then about my mother:

When I was born, nearly everyone in my family had escaped Poland and the Holocaust. Every adult not only had to become an American and to learn English, but every one of them carried trauma. The elders spoke English with exotic Polish or German accents, the younger ones spoke standard American English with perhaps an exotic hint, but all carried the burden of having come to the United States as refugees.

As the years passed, of course, immigrants died and Americans were born. The death of my mother marks the passing of the very last immigrant who still remembered Poland. Only her first cousin Victor remains, but he left Poland at the age of three. Irene's passing, in other words, marks the end of an era for the extended family.

The successful transition from refugee status to native-born Americans was inevitable and good, but it also marks a moment of sadness with its loss of experience, color, and memory.

My mother came to appreciate her birth country, returning to Poland first in the 1950s and then, in her later years, spending about a month there annually, enjoying friendships and the arts, proud of speaking a distinctively elegant pre-war Polish. She also served for decades as the president and principal patron of the American Association of Polish Jewish Studies. Interestingly, in later years her friends increasingly tended to be found in Poland, as she felt very much at home in her natal town, delighting in the language, food, and high culture. Her wonderful companion and assistant of recent years, Agata Bogatek, is Polish; I thank her for the great service she faithfully provided.

Finally, about Irene the personality, the friend, the wife, the mother and grandmother.

To start, her personality: My mother was distinctly a character. She would not take no for an answer and wore down innumerable gate agents and park rangers to get her way. Against all odds, she insisted that her many excursions to casinos netted large sums. She officially quit smoking about 1970 but carried on clandestinely for over the next fifty years, to the bemusement of the entire household. At the 70th wedding anniversary, she made sure we all knew that she was still pondering if she had made the right choice in marrying Richard.

As friend: She had a talent for friendships, charming strangers and keeping those close to her by her side. Especially with age, she developed an imperious demeanor that we relatives found a bit exasperating but delighted the outside world. Through middle age, she had friends and correspondences on several continents. As she grew older, though she complained about their disappearing on her, she managed to find new friends, especially in Poland.

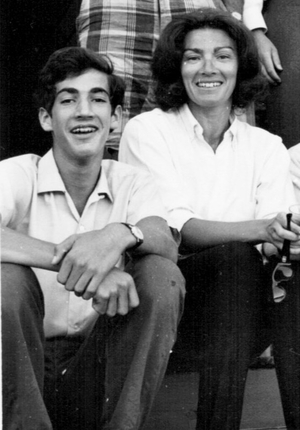

Irene and Daniel, 1964. |

As mother: Irene was not exactly a helicopter parent. She had us children when young; being extroverted and social, she preferred that we find our own way in the world. Thus, I changed trains on my own traveling in Switzerland at the tender age of seven. I made my own breakfasts. I learned to swim by being thrown off a float. I got my driver's permit one day after my 16th birthday. Busy as friend and wife, motherhood was something of a side-activity – which was fine with us, her children.

Grand-motherhood suited her better, coming when she was older and not demanding her full-time attention. I cannot count the times my mother solemnly announced that my having fathered Sarah, Anna, and Elizabeth was the best thing I ever did in my life. She reveled in her granddaughters, perhaps in part seeing them as compensation for the still-born daughter.

Irene at her 90th birthday party with her three grand-daughters (from left): Elizabeth, Sarah, Anna. |

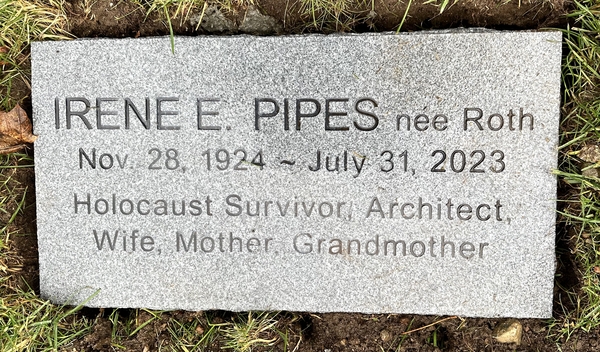

I conclude by recalling her oft-stated wish to be buried next to Richard with the simple epitaph, "His Wife." I never agreed to this, hinting that I had something better in mind, and that will be: "Irene Eugenia Pipes, née Roth. 1924-2023. Holocaust Survivor. Wife, Mother, Grandmother, Great-grandmother."

Aug. 2, 2023 update: Irene's sister's daughter Denise Tennen read out an "Ode to Irene" at her funeral. It was originally composed on the occasion of Irene's 80th birthday in 2004, a collaborative effort led by Denise that included Paula Roberts, Sarah Pipes, Anna Pipes and Ari O'Sullivan at a coffee shop in Cambridge, then slightly revised by Denise.

There once was a girl name Irene,

Of Warsaw she was the queen.

She eschewed girlish toys

To play with the boys

And grew up to conquer Filene's.At sports she always excelled:

Swimming, skiing – I could just kvell.

Especially with tennis

She could be quite a menace

With a serve like a bat out of hell.Sibling squabbles there were for sure,

With bad behavior galore.

And though she'd be mean

And her sister would scream

In the end there's support to the core.Beautiful, stately and proud,

Her accidents drew quite a crowd.

She smashes and bashes,

Never totally crashes,

And always emerges unbowed.A double blind date at Cornell

Would lead to wedding bells.

Sparring with Dick,

That became her schtick.

She's grown like a pearl in a shell.In Moscow the commies would try

With liquor her husband to ply.

He'd pass her his drink,

She'd never blink.

Dick's secret weapon was I-Rene, with an architect's gleam.

Her choice in high tech is supreme.

As a designer

There is no one finer

Her houses are the crème de la creamSo sing ho for Empress Irene

From all who share her genes,

From Warsaw to Boston,

She never gets lost in 'em

And she finally uses sunscreen.

Aug. 7, 2023 update: American Friends of POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews sent this letter to me:

Aug. 31, 2023 update: Boston's Jewish Journal ran an informative obituary by Penny Shwartz, minutely amended here:

Irene Pipes, 98: Champion of fostering Jewish-Polish relations

Irene Pipes. |

By the time Irene Pipes and her husband Richard were starting a family in 1949, the Jewish refugees had become fully assimilated Americans.

It had been only nine years since each had fled Nazi-occupied Poland with their families, who settled in New York. After meeting in college and getting married, the young couple was about to enter the Ivy League world of Harvard and Cambridge, and looked only to a bright future. They wanted nothing to do with the traumas of their past.

The only time their oldest son Daniel and his brother Steven heard Polish was when their family gathered with relatives and when their parents didn't want them to understand what they were saying to each other.

"Polish was a secret language," Daniel told the Jewish Journal in a conversation recalling his mother Irene, who died July 31 in Cambridge at age 98.

Richard, her beloved husband and companion for some 72 years of marriage, died five years ago. The career-long Harvard University professor was a scholar of Russian and Soviet history and an adviser to the Reagan administration on Soviet and Eastern European policy.

In ways Irene would never have imagined, she discovered a level of comfort and pleasure in her native Warsaw, Daniel wrote in a published remembrance. It was a transformation that began in the 1950s and continued for the rest of her life, said Daniel Pipes, president of the Middle East Forum and a prominent commentator on the region.

"She felt very much at home in her native town, delighting in the language, food, and high culture," he wrote.

Over time, she became an early and influential champion of fostering Jewish-Polish relations and of the re-emergence of Jewish life in Poland.

Her advocacy included serving as president of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies since the 1990s and she played a leading role in the production of Gazeta, the association's notable quarterly journal, Antony Polonsky wrote in a comment to Daniel Pipes' remembrance. Polonsky is an emeritus professor of Holocaust and Jewish studies at Brandeis University and chief historian at Warsaw's POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

"She employed her considerable diplomatic talents to foster dialogue on difficult and divisive issues," Polonsky wrote.

Her contributions to Polish-Jewish understanding earned her the Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland, noted Polonsky, who worked closely with Irene at the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies.

Daniel Pipes realized only recently that his mother's embrace of Poland stood out among Jewish Polish refugees and survivors, who did not want to visit their native country having survived persecution against Jews and in some cases, the deadly Holocaust.

Over time, Irene began to spend one month every year in Warsaw, Daniel Pipes said. His father was a reluctant co-traveler, being among those who would have preferred to spend less time there. "She was appreciated there as someone who carried this pre-war, pre-fascist, pre-Communist culture," he recalled about his mother.

There was also a touch of nostalgia, Daniel Pipes said.

Born Irena Eugenia Roth in Warsaw on Nov. 28, 1924, she recalled a happy childhood with her younger sister, Hanna, enjoying a financially comfortable lifestyle. When Daniel Pipes and his family traveled to Warsaw with his mother, she was eager to take them to the pastry shop cafe she had frequented with her grandmother many decades before.

She developed close friendships with college professors and people in the arts, including Krzysztof Penderecki, a prominent classical composer, and his wife, Elzbieta.

Her friendship with professor Józef Andrzej Gierowski, the rector of Jagiellonian University in Krakow, led to her keen interest in the university's Institute for Jewish Studies. Nearly a decade ago, she established a research center on the history and culture of Polish Jewry and Polish-Jewish relations. She also funded a chair at Bar-Ilan University in honor of her parents, The Marcell and Maria Roth Chair in the History and Culture of Polish Jewry.

She her husband, Richard, and Daniel Pipes were guests at the launch of the center, with a two-day program in October of 2014 that included talks by Richard and Daniel, according to professor Michal Galas, the center's director appointed from its founding.

Edyta Gawron, a professor at the Jewish Institute, recalled fond conversations she had with Irene over the course of her many visits to Krakow, with Irene speaking in fluent Polish about her favorite food and places she enjoyed visiting.

She was always eager to speak with young people taking Jewish studies classes. "I think she admired their determination to commemorate the Jewish life in Poland," Gawron said in an email.

Irene stayed up-to-date on current events in Poland, both her son and Polonsky said. Despite being saddened by the recent rise of populism there, she never lost her sense of hope for Poland's future and in Jewish-Polish relations.

"She remained optimistic, convinced that people of good will would find common ground," Polonsky wrote. "She will be sorely missed."

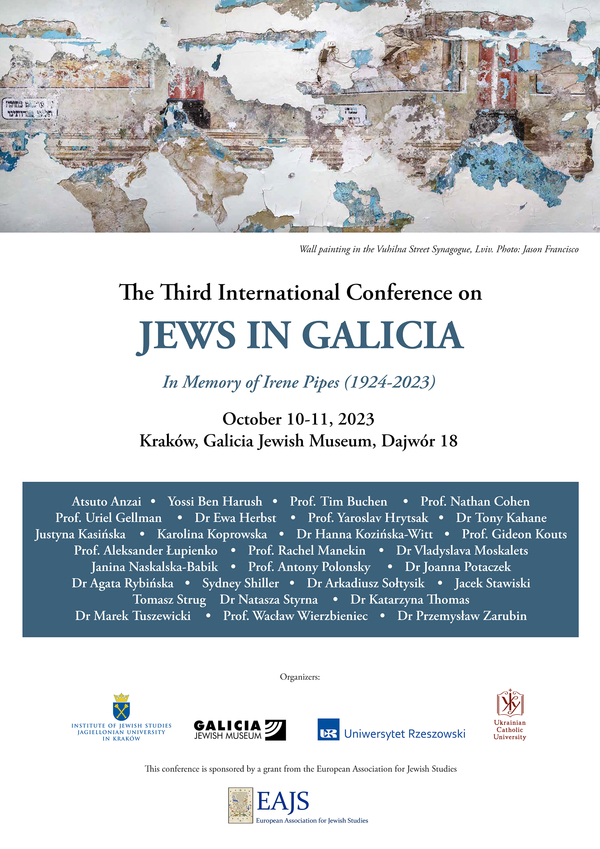

Oct. 10, 2023 update: Prof. Michał Galas (director of the Marcell and Maria Roth Center for the Research on the History and Culture of Polish Jewry and Polish-Jewish Relations at the Institute of Jewish Studies of the Jagiellonian University in Krakow) informs me that the third international conference on Jews in Galicia taking place today and tomorrow is dedicated to the memory of Irene Pipes.

Nov. 15, 2023 update: Antony Polonsky, emeritus professor of Holocaust Studies at Brandeis University and chief historian of the Global Educational Outreach Project at Polin (the museum of Polish Jewish history in Warsaw) delivered this talk today at the Jagiellonian University, describing Irene Pipes' professional work:

Irene Pipes and Polish-Jewish Relations

Irene Pipes, who died aged 98 on 31 July 2023 made a major contribution to the development of Polish-Jewish Studies and Polish-Jewish understanding. She did this, above all as President of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies from the early 1990s and through her support for the Roth Center for the History and Culture of Polish Jews and Polish-Jewish Relations in the Department of Jewish Studies at the Faculty of History of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, established in 2013. which is headed by Professor Michał Galas. She also provided considerable assistance to the Center for Jewish Culture in Kraków, headed by Joachim Russek. In addition she has supported a significant number of scholars of the Polish-Jewish past in Poland.

Irene's fostering of Polish Jewish studies also extended to Israel where in 2012 she established the Marcell and Maria Roth Chair in the History and Culture of Polish Jewry from the Middle Ages to the present at Bar Ilan University, currently held by Gershon Bacon.

Irene came from a family that was well integrated in Polish society but retained strong Jewish ties. She herself was devoted to her Jewish heritage and was well acquainted with Polish culture with a particular love of Polish popular and cabaret songs of the 1930s with which she grew up. Irene was thus an ideal intermediary in the attempts from the mid-1980s to alleviate the tensions and hostility between Poles and Jews, insofar as these are discrete groups, which is not always the case. In her view, the way forward was for both Poles and Jews to look again at their common history and recognize both its positive and negative aspects.

Irene's family had miraculously escaped from Poland in 1940. Her father, Marcell was a prominent Polish industrialist involved in the chemical industry, representing the German firm I.G. Farben. He came from Busk in East Galicia while her mother, Maria, was from Warsaw where the couple settled after Polish independence. As a native of Galicia, in 1923 Marcell had the choice of opting for Polish or Austrian citizenship. He chose the latter, which meant that after the Anschluss in March 1938 he became a German citizen. As a result, he was one of those interned by the Polish government in the concentration camp at Bereza Kartuska in the run-up to the German invasion of Poland in September 1939. The Roth family lived very comfortably and normally would have hoped to survive the Nazi occupation in Warsaw.

However since Marcell Roth had been interned, his wife Maria decided to drive eastwards with her two daughters in their Hispano-Sousa, which was something of a phenomenon in pre-war Warsaw. She was certainly one of the first women in interwar Warsaw to obtain a driving license. The car was confiscated when they entered the area of Poland occupied by the Soviets, but they succeeded in making their way to Vilna, which was incorporated into neutral Lithuania on 28 October 1939 and where they had agreed to meet Marcell should he be released, which in fact took place.

After several weeks, they were reunited and, with the help of Marcell's New York-based brother, were able to fly to Stockholm and take an ocean liner to New York. Maria, who had behaved heroically throughout this ordeal now retreated to her first class cabin and refused to emerge for the duration of the voyage. As Irene explained, she did not have a change of clothing and therefore was not willing to be seen in the dining room.

Irene, who was fifteen when she arrived in the United States, rapidly adapted to the new conditions in which she found herself and, after graduating from high school in New York, began to study architecture at Cornell University. It was here she met her future husband Richard, who had been drafted into the Army Air Corps and sent to study Russian at Cornell. He came from a similarly acculturated background and his family had had a similarly miraculous escape from Poland.

Dick's father, who had fought in the Piłsudski Legions and who in the 1930s had been a supplier of colonial goods to the Polish army, had acquired Bolivian passports from one of his business contacts. Using these, the Pipes family had been able in 1940 to make their way to Italy, from where, after a year, they were able to sail to the United States. As is well known, Dick, who died in 2018, had a distinguished career serving as Chairman of the Russian Research Center at Harvard and spending two years in Washington as a member of the National Security Council advising President Ronald Reagan on the Soviet and East European affairs.

Irene and Dick were devoted to each other throughout the seventy-two years of their marriage, although given that both had extremely strong personalities, they sometimes clashed. In his autobiography Vixi Dick wrote of her as follows:

We complemented each other perfectly: to paraphrase Voltaire, she assumed command of the earth, I of the clouds, and between us, kept our little universe in good order. Her charm, beauty, and joie de vivre have never faded for me.

My marriage was for me a continuous source of joy and strength. In a book which I dedicated to her after we had celebrated our golden wedding anniversary I thanked her for 'having created for me ideal conditions to pursue scholarship'.

Given their own extraordinary escapes and the fact that the majority of their families had perished in the Holocaust, both Irene and Dick were devoted to their Polish-Jewish heritage. As part of the polonized minority within Polish Jewry, they also had a strong feeling for Polish culture and had many Polish friends. Irene revisited Poland for the first time in the 1950s and after the end of communism spent a considerable amount of time here, delighting in the language, food, and culture. She was particularly proud of her distinctively elegant pre-war Polish. In her last years she was devotedly cared for by Agata Bogatek from Warsaw.

As President of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies from the early 1990s, Irene employed her considerable diplomatic talents to foster dialogue and discussion in an open manner on difficult and divisive issues. She also played an important role in the production of the Association's quarterly newsletter, Gazeta, and was a consistent supporter of its yearbook, Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry.

The final issue of "Gazeta," December 2022. |

She also contributed significantly to the establishment of the Roth Center for the History and Culture of Polish Jews and Polish-Jewish Relations in the Department of Jewish Studies at the Faculty of History of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, which is named after her family. This followed a research trip to Galicia organized by the American Association for Polish Jewish Studies and was also the result of the strong friendship which developed between Irene and under Prof. Józef. Gierowski, Rector of the Jagiellonian University between 1981 and 1987.

The Jagiellonian University had been the first in Poland to open an unit for the interdisciplinary research of the Jewish heritage in Poland when in 1986 it established the Research Center on the History and Culture of Polish Jews under Prof. Gierowski. The main goal of the Center, then located on Gołębia street, was defined by Prof. Gierowski as the organization of reliable and objective research on the Jewish history in Poland without prejudices and stereotypes. Under his direction the Center became an internationally recognized scholarly body and its structure and activities have been a model for other institutions.

In 2000 the Research Center was transformed into the Department of Jewish Studies in the Faculty of History and was relocated in Kazimierz as a part of the attempt to foster the development of this formerly Jewish district.

The establishment in 2013 of the Roth Center has certainly significantly contributed to the work of the Institute. The Center, as an autonomous body within the Institute, has conducted and promoted research on the Jewish heritage in Poland, the role of Polish Jewry in Jewish world and on Polish-Jewish relations through the publication of studies and sources, the organization of national and international conferences as well as through the support of PhD students and post-doctoral scholars from Jagiellonian University and leading institutions in Poland, Israel and around the world.

One of the most important initiatives in which it has been involved was the establishment in 2018 of the annual Józef A. Gierowski and Chone Shmeruk Prize for the best scholarly publication on the history and culture of Jews in Poland. This was organized by the Department of Jewish Studies at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and the Jewish Studies programme at the Marie Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, with the support of the Marcell and Maria Roth Foundation. The prize, which is named after Professor Józef Gierowski and Professor Chone Shmeruk of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, two eminent academics who both made a great contribution to the improvement of Polish-Jewish and Polish-Israel relations and also helped facilitate the development of Jewish studies and research on the history of Polish Jews. This year we will be awarding it for the sixth time.

Irene Pipes's enormous contribution to Polish-Jewish understanding was recognized by the award to her by the Polish government of the Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland. Even as her strength weakened, she remained devoted to the cause of Polish-Jewish understanding and was saddened by the rise of populism in Poland and the threat it posed to an honest and dispassionate evaluation of the complex and sometimes disputed Polish-Jewish past. Until the end she remained optimistic, convinced that people of good will would be able to find common ground and that dialogue and understanding would prevail.

Her son, Daniel, has recalled her oft-stated wish to be buried next to her husband Richard with the simple epitaph on her gravestone, 'His Wife'. Daniel never agreed to this and has promised that on her tomb there will be a more fitting epitaph, "Irene Eugenia Pipes, née Roth. 1924-2023. Holocaust Survivor. Wife, Mother, Grandmother, Great-grandmother." She is survived by her two sons, four grandchildren and one great grandchild. She will be sorely missed.

Dec. 3, 2023 update: That gravestone is now in place.

July 11, 2025 update: Antony Polonsky's appreciation of my mother has now appeared in a book, Jews in Galicia: Studies in Culture, History, and Religion, edited by Michał Galas, Karolina Koprowska, and Wacław Wierzbieniec (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Austeria, 2025).