The crash of EgyptAir's Flight 990 [on Oct. 31] has exposed searing differences between Egyptians and Americans. From the U.S. point of view, the inquiry seems straightforward. Figuring out what went wrong means analyzing the evidence and coming up with the best explanation for the disaster. The American public generally trusts the naval recovery squads, transportation specialists, and law-enforcement officers to do their job.

The Boeing 767-366ER that crashed on Oct. 31, 1999. |

Not so the Egyptian public. Egypt's population profoundly mistrusts its government, and reasonably so given its long history of dictatorship and deception. Egyptians almost universally believe in conspiracy theories, and they nearly always blame the same three culprits: the British, the Americans and/or the Jews. In June 1967, President Gamal Abdel Nasser was caught on tape suggesting to King Hussein of Jordan that the two leaders falsely claim that U.S. and British forces had helped Israel defeat their armies. In 1990, when Egypt's tomato crop went bad, rumor had it that an Egyptian minister of agriculture who was one-quarter Jewish had sabotaged it by importing sterile seeds from Israel.

Conspiracy thinking can be found anywhere, but in the Middle East it dominates at the highest levels of the government, the media, the academy and the religious establishment. And Flight 990 is a particularly inviting target for conspiracy theorists. It carried 33 top Egyptian military officers, plus it originated in New York, the city with the world's largest Jewish population. That's enough to convince many Egyptians that someone purposely brought down the plane to harm Egyptian interests.

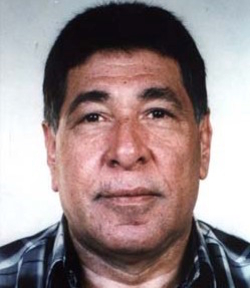

Gamil al-Batouti. |

Thus, Egyptians have been engaged in a surreal debate over whether the culprit was Israeli, American or both. An Egyptian without access to Western media has almost no way of knowing that there is a serious case against Batouti.

The government mostly blames America. The managing editor of the government newspaper Al-Jumhuriya muses about a U.S. surface-to-air missile, or maybe a laser ray, bringing down the airliner. Mahmud Bakri explains in Al-Musawwar, a government-run weekly, how the airliner strayed into a no-fly zone and was instantly destroyed to keep some deadly military information secret. Or maybe, he speculates, New York air traffic controllers intentionally sent the plane in harm's way, a line of reasoning Mr. Bakri finds convincing because Jews "have strong networks of communication at U.S. airports."

Egypt's transportation minister told a parliamentary committee that Boeing, maker of the 767 that crashed, was making a scapegoat of Egypt: "It's the airline production company which tried to defend itself." Added one member of Egypt's parliament: "This 'accident' was deliberate, and the target was the large number of military [officers] onboard the plane."

Opposition dailies mostly blamed Israel. "Evidence of Mossad Involvement in Blowing Up the Egyptian Airliner," screams a huge red banner across the front page of Al-Arabi. The chief editor of Al-Wafd writes on the front page of his newspaper that "Israel's fingers are not far away" from the crash, reasoning that the Jewish state could not pass up the opportunity to eliminate 33 U.S.-trained Egyptian military officers.

That a plane crash arouses such powerful and hostile sentiments in Egypt points to two conclusions. First, 20 years of formal peace with Israel has done next to nothing to improve Egypt's attitudes toward its neighbor.

Second, although Washington is handling the crash inquiry very carefully so as to respect Egyptian sensibilities, such sensitivity cannot contain a brewing crisis. Despite what the State Department likes to calls a "long and close friendship" with Egypt that goes back a quarter century, the gap dividing Egyptians and Americans is huge and perhaps widening. In investigating the crash Washington must follow the truth wherever it leads. And given the larger troubles the investigation has exposed, the U.S. should take a close look at its relationship with Cairo, which has been on autopilot for too long.

Mr. Pipes is director of the Philadelphia-based Middle East Forum and author of The Hidden Hand: Middle East Fears of Conspiracy (St. Martin's, 1996) and Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and where it Comes From (Free Press, 1997).

Mar. 26, 2015 update: In an eerie echo of Flight 990, French prosecutors concluded that Co-pilot Andreas Lubitz deliberately crashed Germanwings Flight 9525 on March 24.

Feb. 2, 2016 update: An article in Al-Qaeda's magazine Masrah, "The September 11 Attacks – The Untold Story," states that the purposeful crash of EgyptAir 990 inspired 9/11. Maayan Groisman summarizes it in the Jerusalem Post:

the inspiration for the September 11 attacks was the story of Gamil al-Batouti ... when then-al-Qaida chief Osama bin Laden heard about the Egyptian plane crash, he asked: "Why didn't he crash it into a nearby building?" pronouncing the idea of targeting buildings.

When bin Laden met with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was identified as "the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks" by the 9/11 Commission Report, the latter presented him with an additional idea: crashing American airplanes.

Before presenting his idea to bin Laden, Sheikh Mohammed started working on a plan to crash 12 American airplanes at once. And so, the final plan implemented by al-Qaida was a combination of Sheikh Mohammed's and bin Laden's ideas: crashing American airplanes into the buildings of the World Trade Center.

July 15, 2025 update: Holman W. Jenkins, Jr. places an Air India crash on June 12 due to pilot error into context:

After 25 years, the Egyptian government still rejects a U.S. finding that the crash of EgyptAir 990 off Long Island was deliberate by its pilot, an act of mass murder killing 217. "The feeling in Egypt," the aviation expert William Langewiesche would later write in a detailed reconstruction, "was that all Arabs were under attack."

Likewise Indonesia issued no finding about a 1997 SilkAir 737 crash that the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board called pilot suicide.

China Eastern Flight 5735? No finding by China's government despite leaked evidence showing the 2022 crash was intentional.

The notorious disappearance of MH370 in 2014? No conclusion from the Malaysian government in a report that left out evidence that the pilot had practiced on his home computer departing from the flight plan in nearly identical fashion, exhausting his fuel and crashing into the sea.

In a telling contrast, French and German authorities briskly concluded that the 2015 crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 was a deliberate act by its first officer. France, in its official report, didn't spare the crew of Air France 447 from criticism for pancaking a perfectly flyable A330 into the South Atlantic at high speed in 2009.

Likewise U.S. and French investigators, in separate reports in 2022, took lead investigator Ethiopia to task for pretending away the critical role of pilot error in the 2019 crash of an Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 MAX.

By now, not blaming local pilots when a First World-made jet crashes is practically a hard-and-fast rule for many governments.